Jory Mickelson

Interview

No two writing journeys are the same. Everyone that picks up the pen does so for different reasons, at different times in their lives. Jory Mickelson’s journey started during a period of uncertainty. He was working in kitchens, having just dropped out of college after deciding he no longer wanted to pursue a degree in visual art, and in his free time he was writing essays and blog posts about topics that he felt passionate about - these were his first steps onto the literary path.

Jory returned to school - Western Washington University in Bellingham - where he pursued an undergraduate degree in Creative Writing paired with a minor in Journalism. During his time at Western, he wrote as an intern for the local newspaper. He continued to share essays and blogs online, and he started writing poetry. He had a whirlwind of emotions raging inside of him, and being able to convert those emotions into poems calmed the winds. From Western, Jory went to the University of Idaho to pursue an MFA. He juggled the duties of his teaching fellowship - teaching English 101 and 102 to freshmen who couldn’t care less - with studying with poets like Robert Wrigley and Edward Hirsch.

Over the seven years that followed his time at the University of Idaho, Jory started a writing group with 3 other Bellingham authors, published Wilderness//Kingdom, and was invited to participate in the Helene Wurlitzer Foundation of New Mexico’s residency program.

Q: What is the Helene Wurlitzer Foundation and how did participating in its residency program help your writing?

A: Helene Wurlitzer was a wealthy lover of art who was a big advocate for the creative minds that resided in New Mexico. She had smaller houses around her main house, and over time she started loaning those houses temporarily to local artists and writers to give them time to focus on their art—this became the Helene Wurlitzer Foundation, and it has continued on long past her death. The residency is 10-12 weeks long, you get one of the houses all to yourself, they help pay for your cost of living, and normally there are social events so you can meet the other writers in the program. Because I was doing my residency during a pandemic, a lot of the social events were cancelled to meet social distancing guidelines. I spent most of the time in my casita (the local term for a small adobe house), just reading and writing. The residency gave me a chance to make some decent headway on the draft for my next book.

Q: Why did you choose the name Wilderness//Kingdom for your first book?

A: The name was inspired by the Jesuit missionaries who came to the area where I grew up. They arrived in the 1840s to convert the local Indigenous communities. These missionaries were led by a Fr. DeSmet, who had taken a ship to the United States from Belgium when he was 16 years old, with a vision in mind of becoming a priest to Indigenous folk. He envisioned a Catholic world free from white influence, and he specifically wanted to mimic what the Jesuit’s had done in South America in the 1600s. These missionaries used the phrase “Wilderness Kingdom'' and that resonated with me as I was writing this book, given that it has a strong rooting in nature themes. Not that I wanted to imitate or glorify colonization and cultural or actual genocide. Rather there is a tension between the ideas we have today about what wilderness is and isn’t. Tension about what makes a kingdom, a country, or an empire. And maybe how these external ideas shape our internal landscapes.

We picked out a few of our favorite poems from Wilderness//Kingdom and asked Jory to give us the story behind them. Here’s what he had to say.

“I was the firstborn in my family, and that made me the “experiment” when it came to rules and restrictions. My parents laid down the laws that they thought they were supposed to enforce, and then they adjusted the severity of those laws for my siblings, oftentimes loosening the reins, giving them more freedom than I ever had. We lived in a rural area that was 30 miles from the nearest anything - movie theatres, malls, fast food restaurants, all the places a teenager wants to go. So, if you couldn’t drive, you were stuck. Prelude was written with my teenage frustration about being isolated in such a small town, a town where I knew everyone and everyone knew me. I felt isolated and alone because of my town’s size and location, but more so I felt isolated because, growing up, I was the only queer person that I knew. There was no one for me to talk to about it.”

“Birds have unintentionally made appearances in my poems over the years and have become a symbol I use when writing about being queer. This might be changing in my current work. Someone told me once mid-Westerners are obsessed with birds. The person went on to say that in the Mid-West there is nothing else to look at. It’s all flat and horizon line. My personal love for birds comes specifically from growing up next to a wildlife refuge, which had hundreds of different kinds of birds to marvel at.

I use the study of birds—ornithology--as a metaphor queerness in this poem. People that love and study birds are able to name the birds they see. In a small town, where everyone knows everyone, most people are able to name the local “queers,” and they do so usually through whispered gossip. It was an often silent or unspoken judgement, but still very much a judgement. The wilderness was one of the few places I could go to let down my guard, be comfortable with my true self. Nature was a place I could feel like the real me for even just a second, and not be the subject of small-town gossip.

Ornithology is about birds, but it has nothing to do with birds.”

“The inspiration for this poem came from two places - The Car That Brought You Here Still Runs by Frances McCue and the ancient Greek poet, Sappho.

Frances McCue co-founded Hugo House in Seattle, which was named after Richard Hugo - a Washingtonian who started the writing program at the University of Montana in Missoula, which was the closest city to my hometown. Richard Hugo was the most famous writer in Montana, even though he wasn’t actually from Montana. Frances McCue’s book, The Car That Brought You Here Still Runs, is about the places that Richard Hugo mentioned in his poems and their history. Frances worked with Mary Randlett - a Pacific Northwest photographer known for taking pictures in black and white - on the book and Randlett took pictures of all the places that Frances was writing about. McCue says in one of her essays that if you want to know the history of the town, look to the cemetery.

Sappho has a quote that talks about being remembered by others in future time, and I love what those words imply because, as adults, we know that that isn’t true. Things, like relationships don’t last forever. I was thinking about this while working on the poem. I thought it was appropriately applicable to the nameless small town in the poem. Not even towns last.

“I live in a condo. There’s a greenbelt and a creek nearby, and when I’m home I spend a lot of time looking at the birds, particularly a pair of robins. Every year they try to build a nest under the porch to our walkup, but because we are constantly walking on it, the nest never turns out how these birds hope it will. So, every year the robins get mad at us, and the young either never hatch or don’t last long. Watching other birds use the imperfect nests throughout the year, finding new uses for them, reminds me of how humans often pick up nests and other nature-made objects and use them as art or decoration.

This poem talks about the struggles of determining how to identify and repurpose things, and the difficulty we have in answering the question, What is art? What is it for?

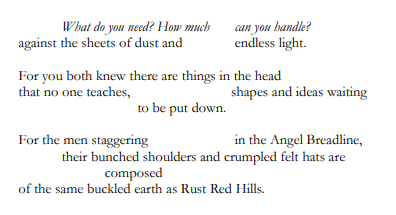

“This poem is a tribute to female artists Dorothea Lange and Georgia O’Keeffe. Dorothea Lange was a photographer from the era of the Great Depression who took pictures in black and white, and Georgia O’Keeffe was an artist from the early 1900s who contributed to the development of modern art in America. They both inspire me because they were both famous women in fields dominated by men. They were women artists during a period that America didn’t have any famous women artists. This poem is describing a fictional conversation between the two of them, had if they ever met, based off quotes both women said during their lifetimes.”

“The narrator of this poem is describing the difficulties in his relationship with his father, and there are several poems throughout the book with that same theme. Whenever people read poetry, they assume that the described events and implied messages are based on truth. But that is not the case with my work. Some of my poems are based on an idea or a theme that aren’t applicable to my real life but I thought was powerful, so I wrote a narrative around it. I take the emotional truth of a situation and arrange the facts and story to emphasize that.

We asked Jory what advice he had for new writers. Here’s what he had to say.

“Read everything. Writers, especially new writers, are obsessed with finding their voice. And so, to avoid having their voice influenced and altered by someone else’s. Young writers, including myself when I started, choose not to read. What I’ve found is that, even when I do a lot of reading, my own voice and style still manages to show in my writing. It shows up in the imagery I describe, the words I use, and the specific stories that I write about. So, my recommendation is to read as much as you can. And to read widely. Especially work by authors you don’t like, because it helps you grow as a writer to be able to read something you don’t like and be able to identify specifically why. Ask yourself, what do I hate about this writing? I also write down things that I like in other writers' work and use it as a source of inspiration later on. There’s so much great writing out there, so many good lessons to be learned, and you won’t be able to find any of it unless you keep reading.

Another thing I would say is, get used to rejection. It’s a major theme of the writing life, and everyone gets rejected at some point or another, often far more than they get approved. It is heartbreaking, but it is an everyday occurrence. There’s a female writer that I like (Kim Liao) who says on her blog that she aims to get 100 rejections a year, and that’s now one of my goals. It’s not that I like being rejected, but rather that I use the rejections to fuel my drive to be successful. To help thicken my skin.

Lastly, find ways to keep being creative. You also need to put your work out there for others to see. Promote your work through social media. Start a blog. Start a literary magazine. Let your passions guide you into new ventures. Experiment with different writing styles. Just keep doing things that will promote your work and keep your creative fire alive, even in the face of rejection. Just because fifty publishers have said no doesn’t mean that there isn’t someone out there who will say yes, who will look at your work and think it’s perfect.”